Hooray for me! I’m one of six winners for the 2019 Odysseyware Educator Impact Award. The good folk at OW flew me out to Philadelphia for the award ceremony, which was very fun and fancy. My acceptance speech is below.

Thank you to the good people at OW for this honor and celebration. I’ve used OW for ten years now, and I’ve been a teacher for ten years now, so in my mind, the growth and improvements of OW are tightly woven with my own growth and improvements as a teacher, and a person.

So, thanks for the award, but more importantly, thank you for being a true working partner. A partner that participates in discussions with me about the nature of education and learning; a partner that listens to and implements suggestions; and a partner that gives suggestions, in part by continually providing me new and better tools to achieve our common goal, helping individual students learn and flourish.

Now my award was given for the category of mastery learning. And as a literature teacher, it shouldn’t be surprising that my philosophy on learning is perhaps best described, in a poem.

To Look At Any Thing John Moffitt

To look at any thing,

If you would know that thing,

You must look at it long:

To look at this green and say,

“I have seen spring in these

Woods,” will not do – you must

Be the thing you see:

You must be the dark snakes of

Stems and ferny plumes of leaves,

You must enter in

To the small silences between

The leaves,

You must take your time

And touch the very peace

They issue from.

Mr Moffitt is not talking about being able to recognize a term or concept well enough to pick it out from three or four answer choices, but to really know something.

And to really know something entails slowing down and looking at it long. Asking, how does this relate to other knowledge in my head? How do I know this is true apart from the lesson telling me so? And most importantly, how does this knowledge help me? Why is it important?

As Mr. Moffitt’s points sunk in over the years, and as OW’s customization tools became increasingly sophisticated and easy to use, I realized the ball was in my court. I could now easily design lessons to encourage the student to slow down and look at things long, to take his time and touch the very peace the information issued from. I could add content to give him new insights into the purpose of the lessons, including how the knowledge and skills attained will improve his life.

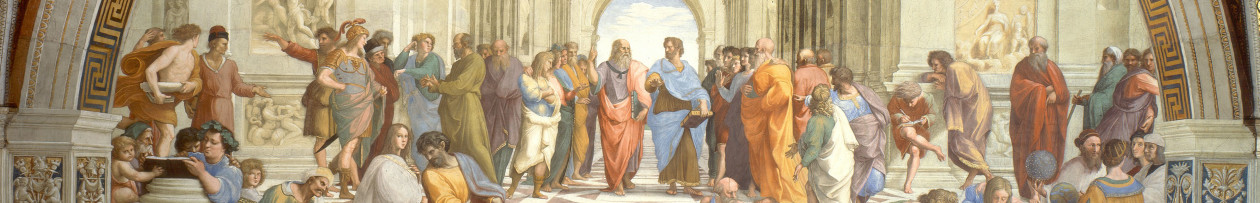

And, in closing, that’s a question worth answering here; how will education improve our student’s life? Well, on a fundamental level, he will understand nature; animate nature, biology; and inanimate nature, physics and chemistry. He will understand man, man as he was, history; as he organizes himself politically, government; and man as he could be or should be, literature. He will understand quantitative methods of measuring the world and predicting its actions, mathematics.

In short, our student, once educated, will understand the underlying principles of his entire world, so that he will be able to operate in the world successfully and comfortably, and manipulate the world to his needs and desires. Isn’t that worth mastering?