Oftentimes people go wrong. But not wrong in the sense that they should have gone north but they went south, they should’ve voted liberal but they voted conservative (or vice versa). Wrong in the sense of just slightly off the mark. The “you’re on to something, but that’s not… quite… it” kind of go wrong.

Today (it seems more than ever) people argue points on history, culture, society, etc., and all too commonly think the other side just “doesn’t see” the obvious; the other side doesn’t think things through; the other side refuses to look at the facts.

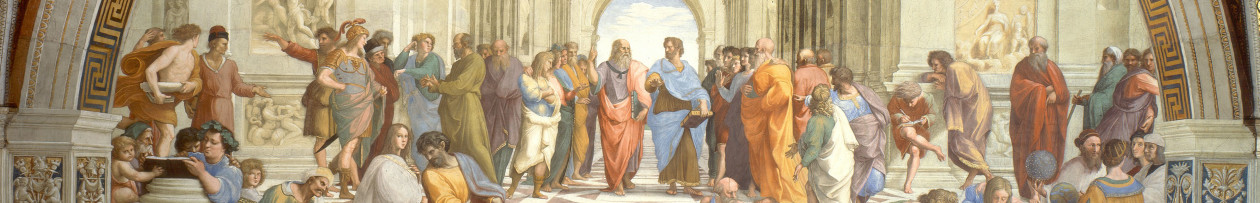

The seeming problem? People live in echo-chambers. People only look at one side of the issue. The idea is that by only exposing yourself to one side of the argument, you are bound to be influenced by that side only. Hence the call to be balanced, look at arguments from both sides and search to find objective, authoritative, fact-checked, science-based, peer-reviewed sources. In a world of Aristotle’s ethos, logos, and pathos, we focus all our might on the ethos.

This is one of those times when we are on to something, but that’s not… quite… it.

I’ve also thought our contentiousness today stemmed from not making an earnest effort to determine the best arguments from the other side. I thought that everyone needs to engage in more antilogy: on Monday argue as best you possibly can your case on the issue, and then on Tuesday argue as best as you possibly can the opposing view on the issue. And while I still think this is a great exercise (when done in earnest), it is missing the essential.

I’ve taught literature, piano, and philosophy for many years, but just recently I also started teaching history, government, and economics, courses more likely to bring up hot-button topics of the day. The difference in these courses is that students tend to have strong views on issues that they hold both confidently and passionately. And while it is true that when I ask a student for the best possible arguments for the other side they rarely have anything worthwhile to say (even after time to research), this isn’t where they really go wrong. My big hint was that, in truth, they don’t have much worthwhile to say about the point they passionately endorse either.

The problem is the depth of their dig for knowledge, not their balance in the digging. As a new history teacher, I’ve had to do a lot of studying myself. I’m finding that you can spend nearly all your time studying an event or era, and each hour of study fills out your knowledge of that era, gives you evidence to think about things you hadn’t thought of before, and generally leads you to think that the common narratives on both sides are often simple caricatures and just generally uninformed.

What I think tends to happen is that if people are concerned about an issue (usually because they already have a strong opinion and to some degree it is being challenged), they dig for information and arguments, but as soon as they find arguments and evidence that support their sensibilities (and that rebuke the challenge), they stop. If they hear of new challenges, they’ll look for more evidence or arguments that support their beliefs, but in the end they are not actually looking for new information so that they can be more thoroughly informed, they are looking to have the superior argument over the people they disagree with. They use the evidence they find like the drunk man uses lamp-posts, for support rather than illumination. (And high school writing encourages this: “Back up the main idea of the paragraph with three supporting facts.”) And of course, when they find enough information to counter the imagined “other side,” they stop.

In short, operating inside any particular group of ideas (one-sided, biased, or “authoritative”) with a strong sense of discovery and understanding, discovery and understanding of what is true so that you can become better informed, will lead to better results (and a less contentious attitude). And of course you will be critical of your sources. The discovery orientation encompasses judging your sources and looking in different places for information. That’s what people genuinely looking for truth and understanding do. The problem isn’t that you don’t see the “other side’s arguments.” The problem is that you don’t look deeply for what is true. It’s entirely possible that you may know the typical arguments of the day, of both sides even, but you still don’t actually know what the heck you are talking about. That’s the problem.